By Will Loux, Senior Vice President, Global Economic Affairs

By Will Loux, Senior Vice President, Global Economic Affairs

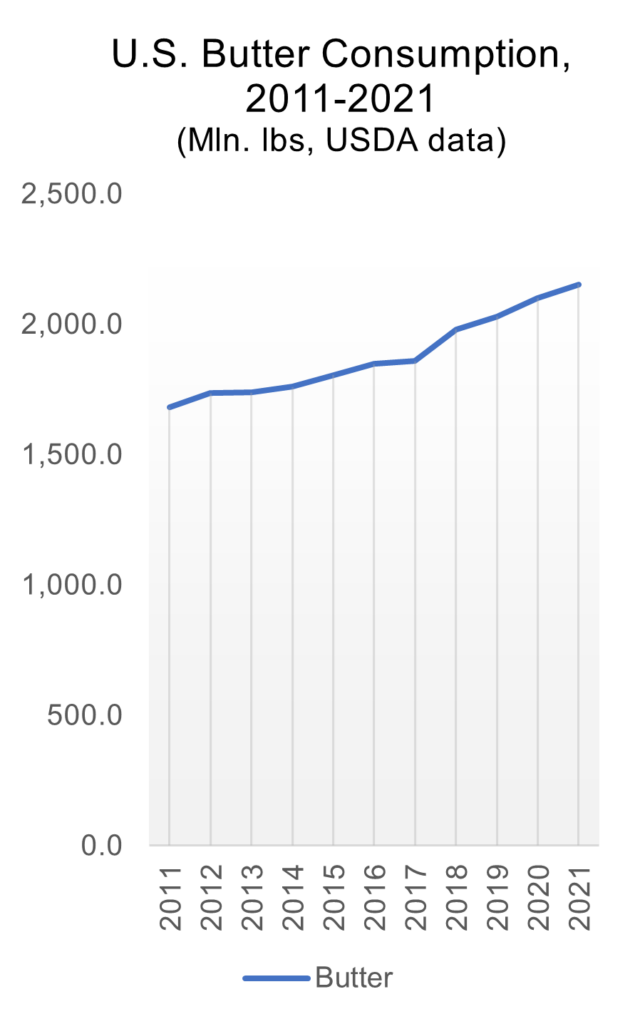

In an article earlier this year, I asked the question whether the U.S. could export its way out of the glut of cream that had filled the market. I posited that while it would take a while for U.S. exports to start growing in earnest due to the high cost of entry for first-time exporters, the market signals were such that the U.S. would inevitably need to sell more butterfat overseas.

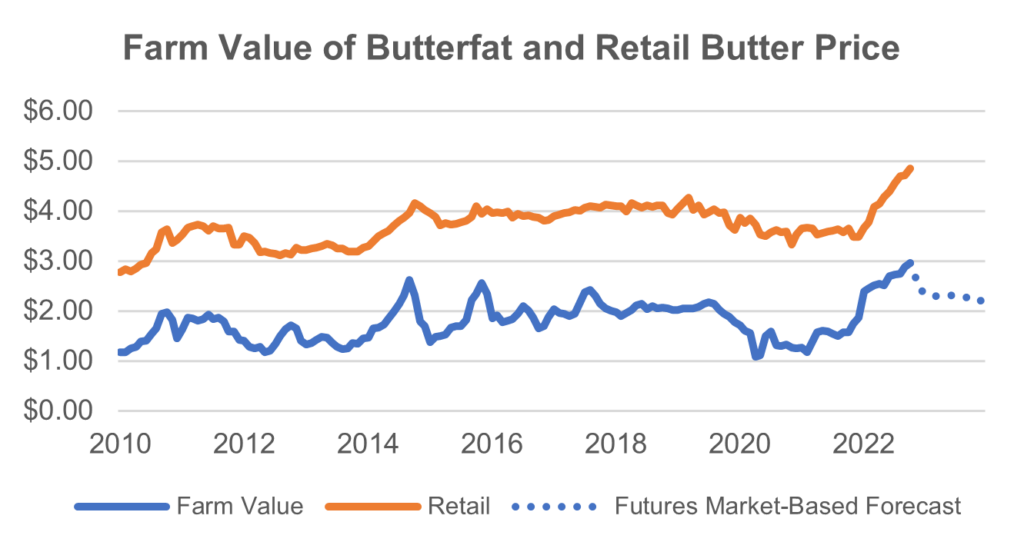

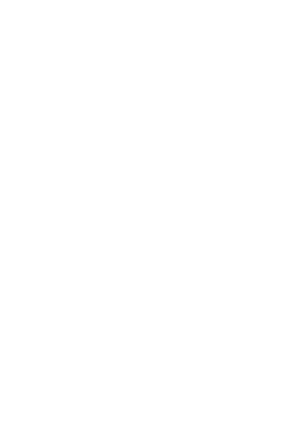

As evidenced by June and July’s export data, that flow of butterfat to international markets has arrived in earnest. June was the U.S.’ largest month of butter exports since 2014, only to be bested just one month later. The U.S. even managed to sell over 2,000 metric tons (MT) of butter to the European Union in July, overcoming a normally cost-prohibitive tariff of 50 cents per pound. The U.S. is also exporting greater volumes of anhydrous milkfat than ever before. In fact, combined exports of butter and anhydrous milkfat (AMF) have grown by more than any other dairy product so far this year on a component-adjusted basis.

The question today is no longer whether the U.S. will export butterfat but rather how much, and can the U.S. become a consistent exporter moving forward?

From a short-term perspective, the path seems clear for the U.S. to sell more butterfat overseas. The U.S. remains highly competitive on price today despite European and New Zealand prices falling. Just as importantly, the U.S. still has plenty of supply available for export despite the surge in exports and solid domestic sales of butter. Simply, the exponential growth in U.S. milkfat tests combined with U.S. dairy herds in expansion mode means the U.S. should have allocation available at an affordable price for international customers for the foreseeable future. While making export spec butter is usually a special run for American manufacturers, U.S. exporters and international buyers are undoubtedly working to get U.S. butterfat products in variety of overseas markets.

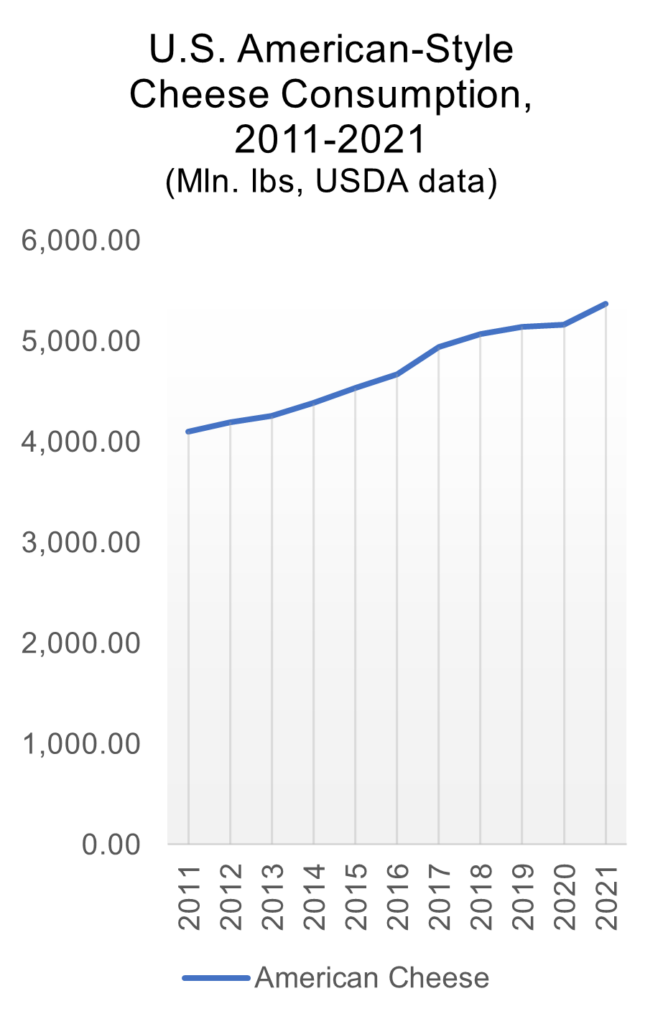

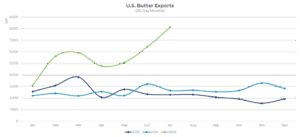

Even from a longer-term perspective, there are plenty of reasons to suggest the U.S. could be undergoing a paradigm shift in favor of greater export business for butter and AMF. The fat-to-protein ratio in milk continues to rise, meaning U.S. cheese manufacturers are now faced with more milkfat than required for cheesemaking. Additionally, the rise in ultra-filtered and protein-fortified beverages will also result more cream moving onto the market. Finally, and just as importantly, the recovery in global demand means international buyers are looking for suppliers besides New Zealand and Europe, the latter of whom have been retreating from commodity fat markets within the last several years.

The investment and strategic foresight to position the U.S. as a consistent player in global butterfat markets, will take plenty of time. However, it wouldn’t be the first time the U.S. dairy industry has identified an opportunity, embraced the challenge, and emerged stronger and more resilient for it.

This column originally appeared in Hoard’s Dairyman Intel on Sept. 15, 2025.

By Christopher Galen, Executive Director, American Butter Institute

By Christopher Galen, Executive Director, American Butter Institute