- Amplified whole milk’s importance in student meals

- Stood against unrealistic EPA regulations

- Shepherded change at the 39th NCIMS

- Fostered H5N1 and New World Screwworm collaboration.

The Regulatory Affairs team has made significant headway this year on longstanding key issues as Washington policymakers take a fresh look at topics that have languished in some cases for decades.

Whole milk is poised to return to school menus after nearly a decade of NMPF effort.

The Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act, sponsored by Reps. GT Thompson, R-PA, and Kim Schrier, D-WA, and Sens. Roger Marshall, R-KS, and Peter Welch, D-VT, has been a top NMPF priority for more than half a decade. Thanks to NMPF’s constant amplification of the latest nutrition science and the benefits of whole milk, the legislation has come farther this year than ever before, passing the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry via voice vote. With multiple avenues available for full congressional approval this year, NMPF continues its advocacy for the legislation, which will return to schools the authority to offer whole and 2% milk in federally funded school meals.

In a win for agriculture, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on Aug. 7 upheld a 2019 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency rule that exempted air emissions from animal waste at farms from select reporting requirements subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986, or EPCRA. EPCRA reporting requirements are tied closely to the reporting requirements for the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980, or CERCLA, which is commonly known as the Superfund statute. Both CERCLA and EPCRA include reporting requirements for releases of hazardous substances to the environment that NMPF has successfully contested for years.

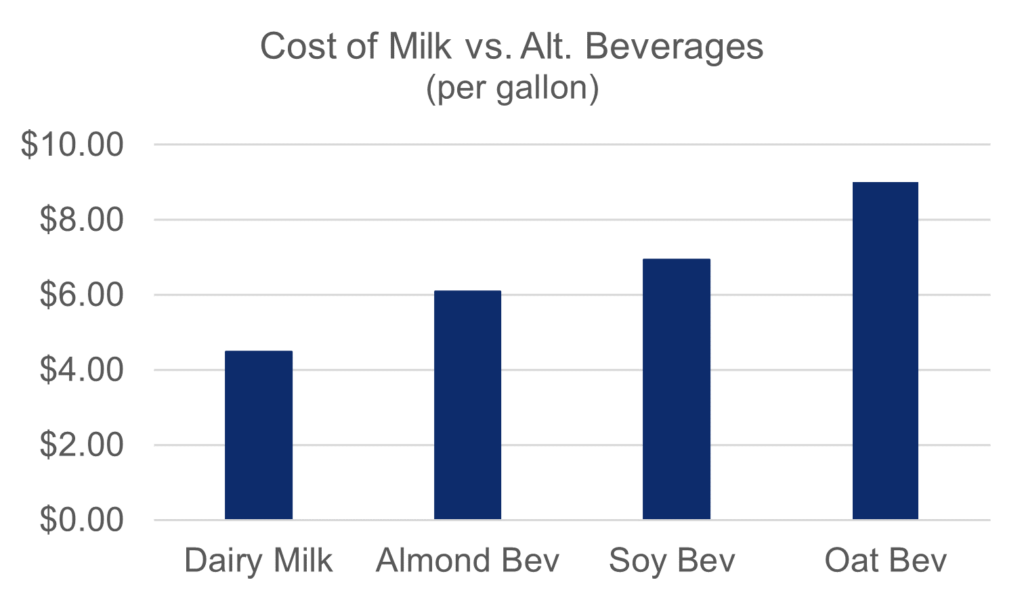

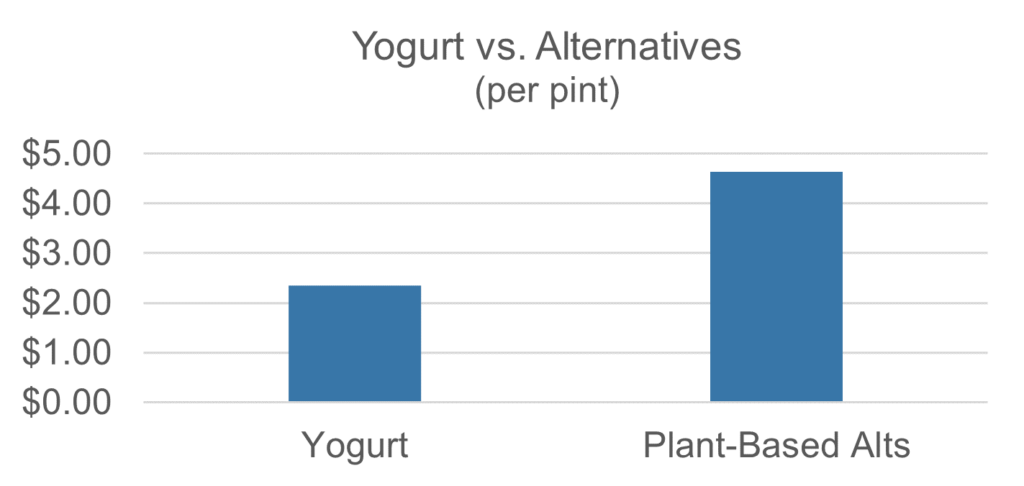

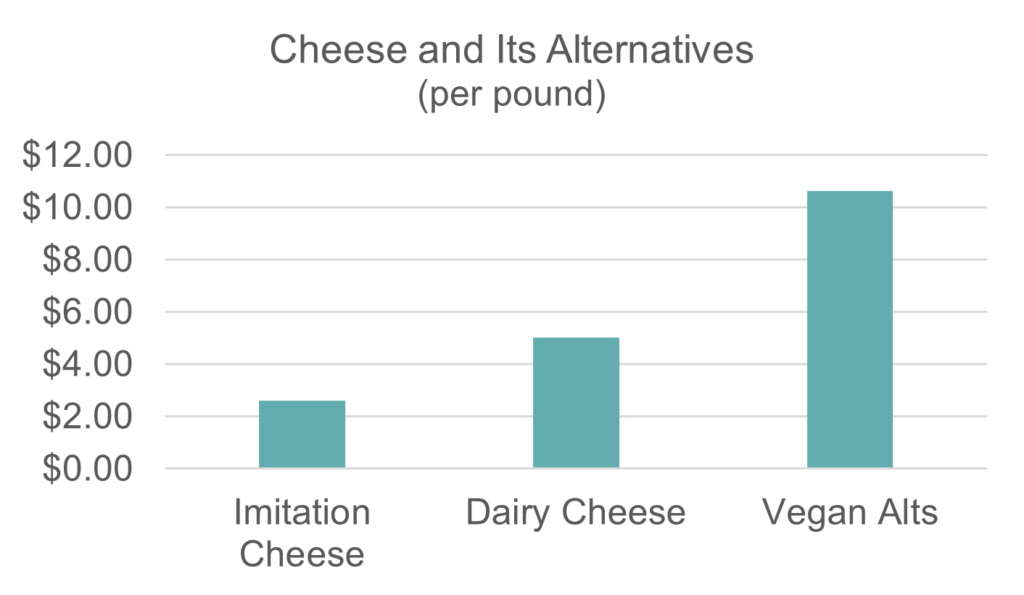

For the second time on the same rule, NMPF filed comments July 11 to the Department of Health and Human Services opposing FDA’s proposed Front-of-Pack labeling rule as well as two proposed plant-based labeling guidance documents. These comments responded to a request for information as part of HHS’ deregulatory initiative begun by a Trump Administration executive order, and echo comments NMPF submitted directly to FDA in January about the proposed rules and guidance.

In its comments to HHS, NMPF states that FDA’s Front-of-Pack nutrition labeling scheme is a highly flawed, unlawful approach to educating consumers about food nutritional profiles. Because the front-of-pack label would only list saturated fat, sodium and added sugar, consumers will get an incomplete picture of that food’s nutritional profile. In its separate comments to HHS on plant-based guidance, NMPF pointed to ample evidence that mislabeling has led to confusion among consumers regarding the nutritional deficiencies of plant-based alternatives and that there are negative human health consequences as result of that confusion. NMPF helped deliver favorable outcomes for nine proposals it submitted on behalf of its members, including a standard for bulk-tank cleaning that’s better aligned with milk-truck standards, at the 39th National Conference on Interstate Milk Shipments, which met April 11-16 in Minneapolis. The conference tackled important issues facing FDA’s National Grade “A” Milk Program, the Grade “A” Milk Pasteurized Milk Ordinance (PMO) and related documents.

Support for eliminating H5N1 in dairy herds and rapidly developing an approved H5N1 vaccine for dairy cattle has continued this year. NMPF created an H5N1 Vaccine Working Group to help inform about potential H5N1 vaccination strategies for dairy cattle which may include target populations, vaccination protocols, surveillance frameworks, and communication needs for stakeholders. NMPF has also worked closely with USDA and FDA to monitor and prepare for a potential New World Screwworm infestation. A fact sheet for farmers to know what to look for in their herds and what to do if they suspect a case of NWS on their farm is available online, and NMPF will update members as new information emerges.

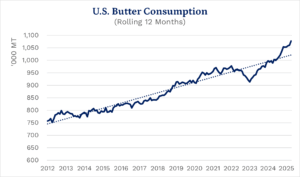

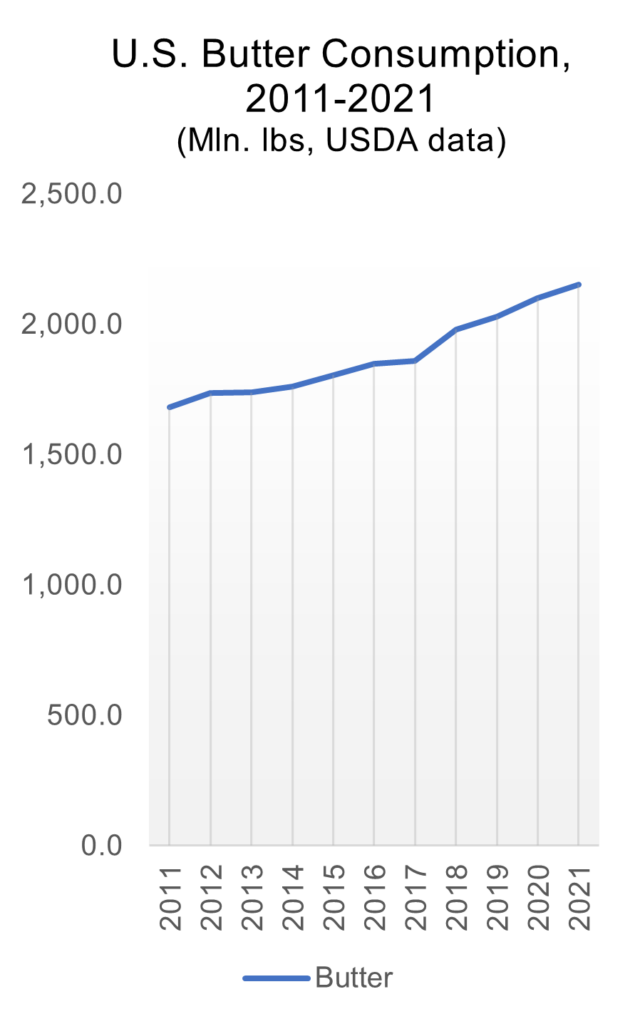

By Christopher Galen, Executive Director, American Butter Institute

By Christopher Galen, Executive Director, American Butter Institute